The Dad Box

The Unbroken Horizon by Jenny Brav is coming out August 15th. In it, Sarah Baum—a humanitarian nurse working in conflict zones— unravels after a Sudanese boy she’s befriended dies of malaria. This event triggers her unprocessed grief over her father’s passing of a sudden heart attack when she was young. While she’s working through her childhood wounds, she finds a box of her father’s things, replete with clues to his ancestral past.

In this autobiographical piece, Brav details the events in her own life that inspired her character’s journey.

The Dad Box

May 1999, Paris

Roaming from room to room in my childhood apartment, I felt dazed. Grief gripped my heart. Made it hard to breathe. My mind was numb with incomprehension. A week prior, I’d been in Nepal, trading upbeat emails with Mom about the latest Gerard Depardieu movie she was subtitling. Now, all that was left of her was the mountain of things my older sister Laura and I had to sort through.

At twenty-five, I was no stranger to death. My father had passed away, also of a sudden heart attack, when I was eight. The next year, my favorite grade school teacher died after being thrown from her horse, and my best friend’s dad was killed in a motorcycle accident. When I was nineteen, my beloved aunt lost an eight-year battle with breast cancer.

But it never got easier. While some people (like Laura) found comfort in focusing on practical matters during times of intense loss, I wasn’t one of them. Instead, I got emotional and needed to work through my feelings first. Every item I picked up had a string of memories attached to it. The notebook where Mom kept score to our mostly friendly Scrabble games. Her handwritten recipes that we’d spent hours poring over and experimenting with. Books she’d read to us way past the age of bedtime stories.

Getting choked up, I decided to go into the closet my mother had converted into her tool shed. Fewer memories. She was the handy one in the family, and it was one of three of her many passions I didn’t share with her (the other two being knitting and sewing). After sorting all her tools into giveaway/sell piles, I got the step ladder to start clearing the upper shelves. Behind an electric saw, I saw an unmarked box. I had an intuitive sense that I did not want to open it alone.

“Laura, can you come here?” I called out.

“What?! I was sorting the clothes!” she responded grumpily as she trudged down the hall. With only three weeks to vacate the rented apartment, we were both on edge.

The box was heavy, and we dragged it to Mom’s king-sized bed, clearing out space in the middle of her dresses and knitted sweaters. I opened the cardboard flaps with trembling hands.

Nothing could have prepared me for the contents of that box. Or the inner journey it would later set in motion.

Inside it, we discovered a world of Dad we hadn’t known existed.

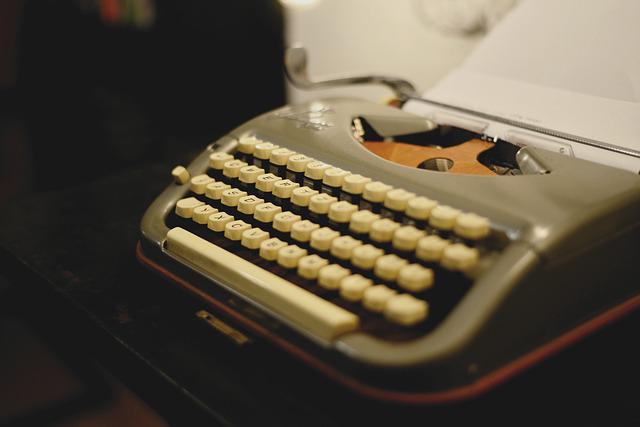

Stack upon stack of what looked like unfinished playscripts. Typed on his old, metallic gray typewriter with the round keys that stuck, the uneven lettering weaving jagged lines across the page. I ran my finger over the print as though it were braille. Not sure I had the strength to peruse these now, I looked up at Laura, a question in my eyes. She nodded, took the manuscripts from me, and put them in the “later” pile. Every once in a while, we were wordlessly in sync.

I knew Dad had moved from Los Angeles to Paris in the late 1950s to become a writer, but by the time Laura was born over a decade later, that dream was long buried. He and Mom, a transplant from Wisconsin, had both channeled their wordsmithing talent into a career writing subtitles and voiceover dialogue for films (which was how they met). But this knowing felt vague and distant. I’d never read anything he’d written, although I could sometimes hear the clacking of his typewriter late into the night.

As we continued foraging, we found a folder of articles about the 1968 student uprising in Paris. An avid historian, he’d probably planned to write about it. Underneath, were eight spiral notebooks. One, the pages yellow and stained and the cover hanging by one coil, had “Wayne University” (where Dad had gone to college) stamped on it. The others had the imprint of the Latin Quarter bookstore he bought them at.

My heart started beating faster as I opened them. They were journals. His journals. Starting in 1948, ending twenty years later. Tears streamed down my face. His death had gouged a gaping Dad-shaped hole in my heart that had defined my childhood in so many ways. And also left us with countless unanswered questions, since we knew nobody from his side of the family. Holding the notebooks in my hands, I felt like I’d found the key I’d been searching for most of my life. But I was suddenly terrified of looking, not sure what I might find there.

Laura hugged me, and held me until my wracking sobs subsided. As we pulled away, I saw that her hazel eyes were brimming with tears. I was tempted to stroke her long, dark blond hair, but—knowing she might pull back and that I couldn’t handle it right then—decided not to.

“I wish we had time to go through these, but we’ve got so much to do… Should we see what else is in here?” She asked, more hesitantly than was her norm. I nodded mutely.

We both gagged as we unearthed a graphic porn magazine from under the journals. We promptly threw it in the trash pile.

“Eww! Why on earth would Mom keep that?”

“You know her… Probably shoved all of Dad’s stuff into this box, planning to go through it later. And of course, later never came.” On that note, we decided to take an ice cream break, and come back to it “later” (which, of course, turned into years—we were our mother’s daughters, after all).

After we’d given away or sold most of Mom’s things, the Dad Box wound up being one of forty we shipped to our aunt’s house in Maine. At that time, Laura was on mission with Doctors Without Borders in Peru, and I was on a Fulbright Scholarship in Nepal. We were both nomadic, and I had just lost my only homebase. We figured it might be at least a decade before we were reunited with those boxes, and called it our ten-year plan.

Summer 2007, (near) Rome, Italy

Not quite ten, as it turned out. Eight years later, our well-traveled boxes flew across the Atlantic once again. Their end destination: the small mountain village outside of Rome where I was living with my partner. Our Maine aunt had died of lung cancer the year before and her husband was now downsizing, so we needed to get our things out. At that point, I had more space than Laura. After working with Doctors Without Borders in Africa and the Middle East, she had moved back to Paris. Her apartment was the size of a closet.

I was at a crossroads. My two-year job setting up a project in Nepal for a non-profit had ended, and I was having trouble breaking into the job market in Rome. I was feeling lost. Untethered. With time to reflect—a luxury I hadn’t had in years—my parents’ absence became palpable. As I wrote in my journal at the time:

“With every death in the family, every lapse of memory, I lose a little more of my history. With no creation story to make sense of where I came from, I forge ahead blindly.”

I found a French therapist in Rome who specialized in transgenerational therapy, which focused on tracing repetitive patterns and significant dates in the genealogy. I began reading Dad’s journals with the determination of a scientist. Highlighter and yellow post-it in hand. Panning for information to complete my paternal line, only occasionally letting myself feel the intimacy of this window into my father’s inner world. Scared that I might otherwise be too overwhelmed to continue.

In my father’s story “For a Man to be Born,” I learned that his mother died of an infection when he was thirteen. It wasn’t until he saw his father crying that the reality of his loss sank in. As I read this passage, a memory snuck in, unbidden. Age eight—finding Dad, unmoving, on the toilet seat. Mom returning the next day from an overseas trip, tears streaming down her face. In that moment, I decided I had to comfort her, not the other way around.

I shook my head to clear it of the images, not wanting to get distracted from my mission.

Dad’s world was once more split in two on December 7, 1941. Pearl Harbor Day. My birthday, thirty-two years later. In a journal entry written a few months later, my father wrote: “We live beneath a suspended threat marked WAR. We are all at the crossroads, each ripening, and we may be cut off before we can blossom.”

The next year he interrupted his studies to enlist in the air force, at nineteen. A few months later, his father died of a sudden heart attack. Dad was the only one who made it back for the funeral. My grandfather’s date of death jumped out the page, stunning me. September 9th, 1943. Laura’s birthday, twenty-seven years later.

When Dad finally returned to college, he couldn’t relate to his peers: “I sit and listen to college students harmonizing—sit watching them dance, and know that they are young. That I am still a college student myself is the trick played on many by the war.” Undigested pain slipped into his later manuscripts. “I killed a man.” Bombs dropped from high in the sky. Easy to pretend nothing happened, and yet the scrambling down below told another story.

I didn’t need my therapist’s help to figure out the significance of our birthdays. I felt a momentary stab in my heart as I realized that they both marked traumatic events in my father’s life. And then, I remembered the love. Even as time whitewashed my memories, the way he doted on us remained as vivid as ever. How he asked for a “Daddy sandwich” every night before bedtime, one skinny towheaded daughter on either side of him. Having had kids twenty years later than the majority of his peers (he’d been a confirmed bachelor most of his adult life), when he finally did, he was all in. Perhaps he subconsciously transmuted his pain by bringing new life into the world on those days.

While I’d taken everything else out for my research, his manuscripts were still in the Dad Box stashed under the bed. I felt haunted by the weight of his unfilled writerly dreams. Every time I thought about trying to find some way to finish his writings, I felt a clawing pressure in my chest. After a panic attack had me convinced I was having a heart attack, my therapist suggested it wasn’t my job to fulfill my father’s vision. Just like that, the weight lifted.

I reluctantly let the manuscripts go, and decided to focus on my family tree—which was still so lopsided it was amazing it could stand upright. All I had on my paternal side was his father’s date of death, and the names of his two older brothers.

I joined ancestry.com to garner more information. I was able to trace my grandfather, (whose name I learned was Samuel), back to his birthplace of Kreuzburg, a Jewish shtetl in the Latvian part of Russia, where he was born in 1888. I pieced the rest of the story through interviewing Dad’s friends (and a bit of imagination).

During one of the Russian pogroms of 1905-1906, Samuel fled and made his way to Manchester, England. There he met Hetty, whose family was from the same shtetl as he was. They married in 1914, twenty days after the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. Nine days later, they boarded a ship from Liverpool sailing to the United States. He wasn’t taking any chances, not after what he’d survived. After a short stint in Texas the family settled in Michigan.

Eight years after his arrival in the United States (and two years before my father’s birth), Samuel naturalized and applied for a passport to go to the UK so the boys could meet their grandparents. His grainy, black and white passport photo, found on the internet, is the only picture I have of my paternal grandparents and my uncles as kids.

My father’s family lived one floor up from the shop where Samuel worked as a tailor, above the din of streetcars clanging by, brakes screeching at the red light, horns blaring at the green. I learned from a family friend that Samuel’s education “stemmed from avid, insatiable reading. Although he couldn’t provide material wealth, he bestowed a powerful love of and intellectual curiosity for literature.” Which his youngest son inherited with a vengeance.

Although Dad’s half of the tree was still very sparse, I had to interrupt my research when I got a job working with the United Nations in Nepal. I shoved the Dad Box back under the bed, telling myself I’d get back to it “later.”

Summer-Fall 2010, Rome-Riga-Berkeley

In the summer of 2010, I was once again at a crossroads. My second job with the United Nations in Nepal was ending. So was my relationship. I had started studying Chinese Medicine and holistic healing in Rome, and was feeling called to continue my studies in the Bay Area.

Laura and I met in Rome to disinter the rest of the Mom boxes from where we’d stashed them in my partner’s storage space. With much more perspective than when we packed them over a decade earlier, we were able to donate most of their contents. Laura had a slightly bigger apartment in Paris now, and could store the photo albums and some of the artwork we loved.

Before I left for my next adventure in the United States, we decided to take a pilgrimage to Latvia. We both fell in love with Riga, sometimes referred to as the “Paris of the Baltics.” There was something both familiar in the Art Nouveau architecture and river running through the city, as well as uniquely different in the brightly colored houses and the cheerful knits wrapped around many of the trees.

At my request, we went to Samuel’s birthplace. I’d hoped I could find out more about him. But I was informed by the National Archives in Riga that none “of the vital records of the Jewish community” of Kreuzburg, now Krusptils, had survived. The shtetl had been subsumed by the town around it. A local woman showed us where the Jewish cemetery used to be. All that was left was a weird metallic sculpture. The synagogue was also gone, as were all but three Jewish families. Dispersed. History erased.

Laura and I said our emotional goodbyes back in Paris, and I boarded the plane for San Francisco. Before moving across the Bay to Berkeley, I had one more Dad Box homage to make. In his 1948 journal, I discovered he’d gone to the Golden City, and, as he put it:

“I am madly in love with San Francisco. I am jealous of the hills around which she wraps herself. I’ve viewed her from her towers, peaks, and mountains. I’ve walked her streets, each turn breaking upon vistas of down-plunging or clinging-climbing streets. Somehow the ordinary way of life loses its grubbiness here. The hills have made her people alive, her heights and depths reflected in the character of her children.”

Retracing Dad’s steps, I climbed Twin Peaks, “a pair of beautiful mountain breasts that push against low hanging clouds – one watches as dusk takes over a toy village.” By the time I got there it was nighttime. Below was a shimmering sea of lights spreading far into the distance, the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges breaking the horizontal symmetry. Their gliding beauty was reminiscent of sailboats, and they seemed to be pushing towards the coastline.

At the corner of Laguna and Washington, I searched for his secret golden gate, standing erect in an empty lot, next to a regal palm tree.

“There it stands, a lone gate, closed on nothingness—on a day long passed, on dreams now dust, on lives now worm eaten. It looks out on the park, patiently, defiantly—seeming to say: what was can be again, for this is San Francisco, where dreams do come true.”

Gone were the gate, the empty lot and the palm tree. The only thing left was the park. Can dreams still come true here? I wondered, feeling trepidation at having left everything behind to follow this call to become a holistic healer, in a place I’d never lived and knew no one.

August 2023, Berkeley, CA, USA

I reflect back on the journey I’ve been on. I am now well settled in the Bay Area, the place that captured my father’s heart so many decades ago. And after years of struggle, my dreams have come true. Every day, I get to live my passion: helping my clients heal their childhood and ancestral wounds. I have everything I love at my fingertips: copious organic vegan food. Redwoods and waterfalls. Meditation, conscious dance, and writing communities galore. I live in a cozy apartment with my sweet calico cat.

I’ve learned to access my ancestors through energy rather than evidence, and have put their ghosts to rest. As a writer, I’ve reclaimed the right to tell our story, to erase the erasure. I’ve given voice to some of my father’s most intimate thoughts, and worked through more of my own grief in my fiction writing.

And on August 15, 2023, exactly forty-one years after my father’s death, I will transmute the trauma that split my childhood in two and birth my novel, The Unbroken Horizon, into the world. As I told him in my dedication: “May your thwarted dreams of becoming a writer take flight through me.”

Is my novel semi-autobiographical, you ask? You’ll have to read it to find out.